- Home

- CARMEN CARTER, PETER DAVID, MICHAEL JAN FRIEDMAN

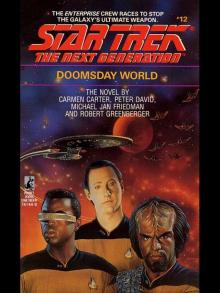

DOOMSDAY WORLD Page 23

DOOMSDAY WORLD Read online

Page 23

And he went on to tell how the ancient Ariantu Empire had collapsed of its own weight, having gone too far too quickly. Of how only a few—the forebears of the Sullurh—had stayed behind to serve as caretakers, until the empire could grow strong again and reclaim them.

“Originally,” Thul said, “the stewardship was to have lasted only a short time. But years became decades, and decades became centuries, and centuries became millennia. During that time, we changed—partly by accident and partly by design, because we knew that it was only a matter of time before the K’Vin would reach out for Kirlos. And when they did, we did not wish to be recognizable as the descendants of their age-old enemies.”

Finally, Thul told them, the K’Vin did come. “And other races came, too. They accepted us as Sullurh, never dreaming that our heritage was so glorious. Long before Kirlosia became divided, we were seen as a trustworthy and hardworking if humble people, quite suitable for employment in the embassies. Nor was it difficult for us to obtain high-ranking posts, ultimately as aides to the ambassadors themselves.

“But all our efforts were in preparation for the Return. Somewhere, we trusted, the Ariantu were still alive as a race, making ready to take back this planet that had once been theirs.” Thul shook his head. “Suddenly our prayers were answered. Four came among us and renewed our sense of purpose. They were Ariantu—true Ariantu, like gods! They gave us a chance to reclaim our heritage, and we seized it as those who are starving might seize at a crust of bread.”

Thul looked at his people, watching for nods or reactions. The little girl, Glora, listened intently. There was a smile on her face. His sister merely nodded, having heard all this before from Thul during private moments, before the troubles began.

“When Lektor told us it was time to retake Kirlos from the alien squatters, we agreed. Gezor and Zamorh and I helped him escalate the enmity between the Federation and the K’Vin Hegemony.” He looked at the Enterprise officers again. “Then, with you three, I found the legendary omega level. I knew it immediately for what it was—the core of our beliefs, the reason Kirlos was so important to the ancient Ariantu. What I didn’t know was just how horrible finding it would be—how it would push our entire world down a road to its own destruction.”

Thul had to stop and collect himself. There were just too many emotions, too much remorse. It all threatened to overwhelm him.

Then he went on—about the appearance of the Ariantu ships and how the Sullurh were eventually rejected by Lektor and the others, how they were deemed inferior, much to Thul’s shame, and finally, how he had unwittingly set the doomsday machine in motion.

“However,” Data interjected, “the doomsday device has been incapacitated. It is possible to establish a new beginning for yourselves. And the first step is to take this information to ambassadors Stephaleh and Gregach. To explain this to them.”

“No!” cried Gezor, trembling with anger—and with fear as well? “I will not face Federation charges of conspiracy and be jailed! I will not be taken from my family and lose everything dear to me!”

Thul walked slowly to the shaking Sullurh and took him in his arms. “Gezor,” he said, “look at me. I have acted as a conscience for our people, acted in what I perceived to be the true Ariantu way. What I have learned is that time has passed; things have changed. We have committed crimes—perhaps terrible crimes. But we must face the consequences with honor, with the nobility that the spacegoing Ariantu have lost. We must go back to the embassies and settle this once and for all.”

Thul’s words were gentle and reassuring, and they had the desired effect. They brought out the courage, the sense of responsibility in his fellow Sullurh.

“And now,” he said, “we must go. Gezor and Zamorh and I.” Like a true leader, Thul walked out of the room, expecting the others to follow.

Data held Worf and Geordi back until Gezor and Zamorh finally moved. Then the trio filed out behind them.

Thul led the group out of the house and down the street to the nearest transmat booth. On the way, Geordi asked Data what he now thought of Thul.

“He is obviously a spiritual leader to these people,” said the android. “I did not suspect this. Did you?”

“No. In fact, this keeps getting weirder and weirder,” Geordi replied. The group had arrived at the transmat station and Thul was programming in coordinates.

“Weirder? Please define the use here.”

“Well, everything seems to be one thing and then, pow—it’s something else. It’s been happening from the minute we beamed down here.”

“Ah. For me, this is not unusual. I am constantly revising my expectations as I observe humans on the Enterprise.”

“So nothing has surprised you on Kirlos?”

“Not true,” Data replied. “As I said, Thul has surprised me, as did the wormhole device. And one more thing.”

“What’s that?” Geordi asked, as they stepped up onto the platform.

“That Lieutenant Worf had a better instinct for dealing with matters here than I originally credited him with. I will remember this the next time I command an away-team mission.”

As the transmat machine began its process, Worf was heard to mutter, “Next time, I will send Keenan.”

Chapter Twenty-two

“THAT IS CORRECT, CAPTAIN,” said Data. “But the proceedings are about to begin. I can tell you more about it later.”

“Very well, Data.” The captain’s voice was clear and calm as it came over the communicator, despite the potentially explosive situation he found himself observing. “But keep me posted, will you?”

“Aye, sir.”

Just then the ambassadors reentered the room.

As she and Gregach came in, all eyes rose to meet them. There were six at the table—the three officers from the Enterprise along with Thul, Zamorh, and Gezor.

Stephaleh avoided Zamorh’s gaze. On a personal level, she would never forgive the Sullurh for the deaths he’d helped cause or for the way in which he’d played her for a fool.

On an official level, however, she’d had to put all that aside. Neither Zamorh nor his people were subject to Federation jurisdiction, so their actions were technically closer to guerrilla warfare than to prosecutable crimes. And now that they’d made public their claim to self-determination, she could hardly let her own feelings get in the way of a just and workable settlement.

Gregach had agreed on this principle, though he seemed to have more difficulty adhering to it. Right now he was glaring at Gezor as if he would have liked to string the Sullurh up by his thumbs.

They took their seats at one end of the table, facing Thul. “We have come to a decision,” she said. “Actually, more than one. And some recommendations as well.”

“First,” said Gregach, “the Sullurh claim to Kirlos appears to be authentic. At least we have discovered no shred of evidence to the contrary.”

“Therefore,” said Stephaleh, “under Federation law, the Sullurh must be granted the right of self-determination. It is their planet; they may do as they wish with it. And if they decide that everyone else is to leave, the Federation will comply.”

Gregach grunted. “The K’Vin Hegemony has no law governing a situation such as this one. We recognize no right of self-rule; otherwise, we would be kept from conquest, which is our life’s blood.” He spread his heavy gray hands. “However, we do not feel compelled to conquer or to maintain dominion over any given place. Until the present time, Kirlos has had value to us. It has been a profitable operation, what with all the trade going on. But now that they know what Kirlos is, and the dangers posed by the Ariantu, K’Vin-side merchants are abandoning our markets in droves—so we no longer have a reason to stay here.”

“Of course,” said Stephaleh, “the Ariantu are now in orbit around Kirlos and they have a competing claim. And there is a certain legitimacy to it. However, two facts dilute their claim: first, and by far the more important, their forebears left this world while yours remained, and poss

ession, as someone once said—someone human, I believe—is nine-tenths of the law; the second fact is that the Ariantu are incapable of governing Kirlos. Divided as they are, they would likely destroy this world and themselves along with it, whereas the indigenous population could carry on in a more peaceful manner.”

“In short,” said Gregach, “Kirlos is yours—if you want it. However, we suggest that you allow the Hegemony and the Federation to aid you in smoothing the transition to Sullurh rule.

“To be sure, we have selfish reasons for wanting to do this. We of the K’Vin Hegemony do not care to have a weapon at our throats, and Kirlos will continue to be a weapon until all its doomsday machinery has been dismantled to our satisfaction. In the case of the Federation . . . well, perhaps they wish to keep a close eye on the K’Vin for a little longer.”

“But the greatest benefit in an orderly transition,” interjected Stephaleh, “will be to the Sullurh. Because when the Ariantu learn of our decision, they will not be pleased. And the Sullurh may need some help in defending this planet—at least, for a number of years.”

“So the plan is this,” Gregach continued. “For five years, Kirlos will remain under the joint protection of the Hegemony and the Federation. After that, the Sullurh may tell us all to go back where we came from.”

“One more thing,” said the Andorian. “On the Federation side, and possibly on the K’Vin side as well, there are those who’ve spent most of their lives on Kirlos. They’ve made homes here; their children have grown up here. You may wish to consider allowing them to remain, but you don’t have to.” She paused, remembering her promise to Lars Trimble. “In your place, I would let them stay.”

Then there was silence. Thul traded glances with Gezor and Zamorh. He must have found agreement there, for a few moments later he nodded to the ambassadors. “How can we say no? To any of it? Your decision is eminently fair. And more generous, perhaps, than we deserve.”

“We also have a suggestion as to how your new government may be set up,” added Gregach, “though, once again, you may do as you like. It seems logical that Thul be named governor, with Zamorh as minister of internal affairs and Gezor as minister of external affairs. Ambassador Stephaleh and I have had much time and opportunity to observe our former aides; we feel that their respective strengths can best be put to use in these positions.”

Thul and Zamorh appeared to accept the recommendation. Gezor, on the other hand, looked a little skeptical—as Gregach had anticipated. But he didn’t refuse, and Stephaleh took that as a sign that the meeting could be brought to a close.

Now all I have to do, she told herself, is inform the Ariantu. . . .

Her aides—the non-Sullurh ones, of course—had set it all up for her. An eight-screen monitor system, through which she could speak with each Ariantu pretender to paac leadership and at the same time maintain a separate tie to Picard on the Enterprise.

Gregach had understood when she asked him not to attend this session. Without question, his presence would only have made a bad situation worse.

However, Thul stood on her right, representing the Sullurh. After all, if they were going to accept responsibility for Kirlos, their leadership had to start here and now.

And in the background, there were the three Starfleet officers. For “moral support,” as La Forge had put it.

“Ariantu,” she began. “We have weighed your claim against that of your on-planet brethren. And we have decided that the Sullurh have a greater right to govern here.”

“No,” said the one called Matat, her features twisting savagely on the viewscreen. “They are nothing—certainly not Ariantu.”

“Nonetheless,” said Stephaleh, “they are here, and they have been here for millennia. You can’t just come back and shove them aside.”

“We will not stand for this,” said another—Keriat, if she recalled correctly. “We reject your decision.”

“We?” echoed the ambassador. “Then which of you will rule Kirlos?”

The question was followed by a flurry of answers—one from each of the seven screens devoted to the Ariantu. She waited until the commotion died down.

“You see?” she said at last. “If there is no we, how can you make a claim, legitimate or otherwise? I suggest that you all go home and reconcile your own differences. Then perhaps you will someday want to return to Kirlos and file a more peaceful claim—with the Sullurh government.

“But be certain that your return is peaceful, my friends. Because the Federation and the K’Vin Hegemony will both be watching over this world. And we have more ships at our disposal than the two you see before you now.”

That set off another spate of curses and threats. But the threats were empty ones. Obviously each ship’s leader knew the weakness of his or her position. Without a single leader, they couldn’t hope to accomplish anything.

The only contingency Kirlos had to fear was irrational behavior. If one of the Ariantu decided to launch a suicide attack just for the hell of it . . .

One by one, they broke communication, until only a single visage remained. It belonged to the one called Lektor.

He looked at Thul. “I will be back,” he said. And somehow it seemed more of a promise than a threat.

Then he vanished like the rest of them.

“Well executed, Ambassador,” said Picard. He paused, turned to someone offscreen for a moment. When he turned back, he was smiling a restrained but satisfied smile. “I am told that the Ariantu are retreating. It seems that we need not worry about them—at least for a while.”

She shrugged. “I have a feeling they won’t come back, peacefully or otherwise. Kirlos was important to them for its mystery, its allure. I think those qualities have been stripped from it by now.”

“Yes,” agreed Picard. “And good riddance.”

Finally they were alone. The Sullurh had gone back to their homes; the Enterprise officers had remained in conference with their captain.

Gregach sat and stared into his drink. Somehow, Stephaleh decided, he seemed younger than her image of him. More vital.

Had some good come of all this after all? she wondered.

“You know,” he said, “my government will no longer allow me to stay on Kirlos.”

She nodded. “I know. Not enough for a full-time ambassador to do here, now that the Sullurh will be taking over the administrative duties. And where do you think you’ll go next?”

He shrugged. “I’m not sure. I would like to think this has worked out well enough for me to be allowed to pick my world. If so, it will be the frontier for me.” He paused. “And you?”

She smiled. “Back to Andor. Oh, I suppose I’ll stay here for a little while to make sure all the pieces fit right. Then I’ll retire—go home and see my family again. Discover if my children will still talk to the mother who abandoned them for a career among the stars.”

“It was a good career,” said Gregach. “And it ended on a high note.”

Her smile broadened. “Thank you, Ambassador. I hope they see it that way as well.”

“You Andorians are an odd lot, I will say that.” He snorted and took a sip from his glass, then ran his tongue over his tusk to lap up a stray drop.

“No odder than you K’Vin.” She rubbed her hands together to work out some kinks that had forced them to curl up. “Will our societies ever see eye to eye, do you think?”

“No, my dear. And I will tell you why. The K’Vin believe in taking action; Federation members think too much. We’ll just have to be satisfied with agreeing not to see eye to eye—and hope that we’ll never come to blows over it.”

“Well said, my friend.” Stephaleh regarded him. “I will miss you, Ambassador.”

He leaned a bit closer. “And I you, Ambassador.”

A comfortable silence.

“I have but one request,” said the K’Vin.

“Which is?”

“In what little time we have left, allow me the chance to win at least one game of dyson.

”

She laughed. “You may try, Gregach. You may try.”

Chapter Twenty-three

BURKE LOOKED UP from his tactical console. “Commander, we are being hailed by the K’Vin embassy.”

“Already? That’s a pleasant change.” Will Riker rose from the captain’s chair and stepped to the center of the bridge. He had resigned himself to a wait of several hours before receiving a response from Kirlos, but less than an hour had passed since Ensign Burke had sent his message to the Sullurh embassy.

When the familiar features of Gezor appeared on the main viewscreen, Riker bowed politely. “Minister, I am honored by your attention to—”

“Don’t call me that!” snapped Gezor, raising his gruff voice to be heard above the chorus of insistent beeps that issued from his desk monitor.

The Sullurh’s curly mop of hair appeared somewhat damp and bedraggled, reminding Riker of Data’s report on the malfunctioning air coolant systems. The entire infrastructure of Kirlosia had been badly shaken by the wormhole’s creation; shock waves had produced the effect of a substantial earthquake, resulting in widespread mechanical breakdowns throughout the underground city.

Gezor shook a fistful of computer printouts at the first officer. “What is all this?”

“I’m simply following the established procedure for arranging the departure of our away team from Kirlos—a Petition for Personnel Departure, a Transfer of Accessory Equipment, a—”

“Yes, yes, I know what they are. I created the damned forms in the first place.” Gezor scattered the papers in an attempt to wipe a trickle of sweat from his forehead. “But I don’t want them. Contact the K’Vin embassy directly about these matters.”

Riker shook his head. “But both the K’Vin and Federation embassy staff insist that the Sullurh embassy is now responsible for all departures from—”

“Oh, go away!” Gezor waved off an aide who edged close to his elbow and plucked anxiously at his sleeve. The administrator turned back to address Riker. “And as for you, Commander, never mind any of the petitions. I’m far too busy to fool with all that nonsense. If you’ll just leave me alone, you can take the team off-planet whenever you please.”

DOOMSDAY WORLD

DOOMSDAY WORLD