- Home

- CARMEN CARTER, PETER DAVID, MICHAEL JAN FRIEDMAN

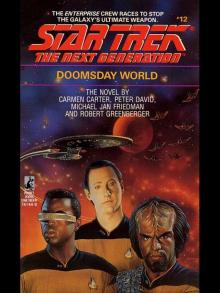

DOOMSDAY WORLD Page 19

DOOMSDAY WORLD Read online

Page 19

Still, she told herself, Lektor has had plenty of time to carry out our plan. Kirlos should be ours for the taking.

The second Ariantu scout was more careful, or perhaps less vindictive, than its predecessor. Following scoutmaster Howul’s lead, the paac ships of the Ariantu jumped into space at a safe distance from the star known as Sydon. Maintaining the tight formation of their passage through the jump tunnel, Arikka directed her fleet toward the outermost planet from the sun.

On Kirlos, the long-range sensors that scanned the sector surrounding Sydon missed the sudden appearance of ten ships within the confines of the solar system. A stealthy approach to the planet’s eternal-night side registered on a few short-range sensors, but these local detectors were supervised by Sullurh employees. And Sullurh hands reached out to silence the alarms before higher-ranking members of the K’Vin and Federation could hear the sound. Unchallenged, the Ariantu armada slipped below the orbiting defense systems of both sides.

Crossing out of the darkness into light, the fleet hovered to a stop over the land that covered Kirlosia. There was no one living on the harsh surface; thus no one looked up and saw the invaders. Except for the Sullurh, none of the inhabitants of the town even knew they had been conquered.

They would know soon enough, thought Arikka as she stroked the arizite pendant at her throat. She was the first of a new line of Ariantu rulers of Kirlos. How many paac mothers would wear her talisman before it had been rubbed smooth? How many generations of her blood kin would walk the tunnels of the subterranean world built by long-dead Ariantu?

Heartmaster Teroon signaled her with a silent wave of his tail. He had established direct contact with their operative on the planet, the one who had prepared the way for the arrival of her paac.

Arikka leaned close to the video monitor, recognizing Lektor. She bared her teeth and said, “We are ready to hunt!”

But her kinsman did not look glad to see her. She could tell by the curl of his lip, the slight quivering of his ears.

“But you’ve come too soon, Mother. Our preparations are incomplete.”

She was surprised. “Then complete them now. How long can it take even your Sullurh fools to set the K’Vin rabble at the throats of Federation curs?”

Arikka saw Lektor’s eyes widen at the rebuke. At least his blood instincts had not been lost during his stay among the degenerate Sullurh.

“We are all fools,” he told her.

The fur on her tail and on her mane bristled, but she had sufficient self-control to keep her eyes hooded. Lektor’s remark bordered on a blood insult; it was not like him to be so careless.

“A Federation warship is on its way back to Kirlos,” the spy went on. “And the K’Vin embassy has requested a warship from the Hegemony. When the two ships cross paths, they will likely fight each other—but not if they hear of an attack on this planet. The threat of a third force could overshadow their hostilities; they might join forces against us.”

“Let them! My children are eager for battle.” Arikka was not about to show fear to anyone. Her kin were young and inexperienced, but the blood of Ariantu hunters ran through their veins. They would rend their enemies by instinct alone when the time came.

“Your fighters are no match for two starships,” Lektor went on. “But there’s no need for a confrontation. If you withdraw the fleet and hide behind the moon Demodron—”

“Enough! This world is mine now. I will not retreat.”

Lektor had apparently gone as far as he dared. Baring his throat, he acknowledged her right to decide. “As you say, Mother. What are your instructions?”

It had only been hours since Thul had left the Ariantu, but it seemed like days. He paced the rooms of his residence, a place no bigger or more comfortable than any of his people’s residences, despite his standing in the community—for among the Sullurh, there were no class distinctions. The only difference between Thul’s home and anyone else’s was the ringing fact of his solitude.

Sullurh rejoiced in family life; it was considered a joy to pass on the mantle of stewardship to each new and eager generation. More than a joy—a sacred trust.

Thul’s other duties, however, had always stood in the way of marriage and progeny. He had been busy with the affairs of the community, enio’lo ceremonies being the least of his burden. The Sullurh had their own laws for settling disputes among themselves, and as their chosen leader, Thul was expected to interpret those laws, to plumb them for a justice that would satisfy all parties concerned.

At the same time, he had responsibilities outside the community. His labors on behalf of Nassa Coleridge, which had enabled him to obtain data regarding the Federation outside Kirlos—data he could never have obtained any other way.

Of course, it had been anything but unpleasant working for the human. At times he had even enjoyed it, and her company as well, to the point that his grief at her passing had been genuine and unadulterated with guile.

Yet he had never lost sight of his reasons for doing what he did. Never had he forgotten that he truly worked for his people, that his efforts were an investment in the day the Ariantu would return.

Then why did he now feel alienated from that purpose, as if it had been taken away from him? Or, worse, had never really been his to begin with?

It made him feel lonely where he had never felt lonely before. It drove home his lack of family with unmerciful force.

And strangeness of strangenesses, the face that kept trying to fill the void was that of Coleridge. Or was it so strange at that?

Other Sullurh had their kin to look to for companionship. Whom did Thul have to look to day after day, other than the human archaeologist?

What’s more, she had been good to him. So many of the aliens treated the Sullurh like inferiors or ignored them, as if they somehow didn’t exist—which was, after all, the condition they had worked to achieve. But Coleridge was different in that regard. She had respected Thul, even liked him, or appeared to.

And he had liked her. Why not admit it? If he had been forewarned about the museum sabotage, if he’d had any idea where and when the next incident was to take place, he would have made certain that Coleridge wasn’t endangered by it. He would have found a way to save her.

Unfortunately, Lektor had not wanted anyone but his group of four to have that foreknowledge. Nor had Coleridge’s presence at the museum made any difference to him; to the Ariantu, she was just another trespasser on Kirlos. Another alien to tread underfoot in their recovery of their ancient outpost planet.

Thul found himself resenting the Ariantu. If he had had any immediate family at all on this world, it had been Coleridge. And it was Lektor’s bunch that had destroyed her. It sounded bizarre when he thought of it that way, but it was true, wasn’t it?

No, he told himself. It is insane. Coleridge was an alien, and the Ariantu are your people. Kinship was not a matter of casual choice; it was buried in the blood, deep and undeniable.

Granted, he felt no real bond with the Ariantu—a disappointment indeed. But it did not mitigate the fact of their common ancestry. Nor did it excuse his resentment toward Lektor and the others.

The Ariantu had done their job, no more, no less. They had held up their end of the bargain; it was up to Thul to do the same.

Suddenly he could no longer tolerate the confines of his residence. He could no longer wait patiently while Lektor bore the entire burden of what happened on Kirlos.

If there was planning to be done, he would help. If work was required, he would do that, too.

Then, if something went wrong, he would have no one to blame but himself.

This time, he didn’t have to knock on the door. Just as he was about to, it opened, startling him.

Lektor, apparently, was just as surprised. He’d drawn his hand back to strike before he realized it was only Thul.

Lowering his arm, he ascended the steps to the street level. Pirrus was right behind him, then Eronn and Naalat. None of them gave the Sullu

rh a second glance.

“Where are you going?” asked Thul, trying not to sound as if he was begging for the information. “Has something happened?”

Naalat looked at him then, breaking stride for just a moment, and snarled. “Something indeed. We are leaving. We have been called back.”

The words were slow to sink in. And before Thul could absorb them in their entirety, the Ariantu had come to stand in the middle of the street. One of them, Pirrus, looked up at the dark, domed sky.

“I don’t understand,” said Thul, following them. “Why are you leaving?”

When Lektor regarded him, it was with narrowed eyes, baleful and bloodred in the darkness beneath his hood.

“Because it has become dangerous here. There will likely be violence—destruction. And since there is nothing else we can do, there is no reason to risk us.” The corners of his mouth pulled back to reveal sharp white fangs. “Do you understand now, Sullurh?”

Thul understood—but wished he didn’t. “What about us? What of Those Who Stayed? Surely we will be beamed up as well.”

Naalat laughed; it was an ugly sound. “Only Ariantu may board an Ariantu vessel.” His eyes were crimson, ablaze with an unholy light. “And you are not Ariantu. Can it be said any more plainly than that?”

Lektor glanced at him as if to silence his arrogance. But Naalat would not be silenced. “Why shouldn’t he know?” he asked. “What difference can it make now?”

Thul addressed Lektor, his voice faltering in his throat. “What does he mean?” he asked.

The Ariantu made a ripping sound in his chest, but something about him seemed to yield. To soften.

“What he means,” explained Lektor, “is that we used you. The Sullurh were never partners in this. You were tools.”

“Tools?” repeated Thul. Now there was a heat growing in him—in his belly, in his face. “But we are Those Who Stayed! We are the ones who sacrificed!” He sputtered. “No one is more Ariantu than we are!”

Lektor snorted. “Really? Look at yourself.” He pulled back his cowl. “Then look at us. And tell me that you are Ariantu.”

Thul shook his head. “You never had any intention, then, of making us participants in your conquest? Of welcoming us into your empire as brothers, as equals?”

Lektor eyed him. Was there shame in his eyes as he answered? “None,” he said. “And if you were truly Ariantu, you would have known that from the beginning.”

Then the figure of Lektor began to sparkle from within, to generate a swarm of frantic ruby-colored particles. And the same thing was happening to the others.

They were departing, leaving the Sullurh to face the threat of the Ariantu ship, alongside the aliens—the trespassers. For in the eyes of the Ariantu, the Sullurh were an alien race as well.

And aliens, Thul knew, were seen only as an inconvenience, just as Coleridge had been an inconvenience back there in the museum.

He could no longer contain the heat that was building inside him. He lashed out in Lektor’s direction, grabbing for his robes, hoping—he didn’t know what. To make him stay? To make him take the Sullurh with him?

But it was too late. The Ariantu had become immaterial—a ghost, sparkling like the embers of a spent hearth fire. And in the next moment, Lektor was gone altogether. They all were gone.

Thul dropped to his knees right there in the street. He felt rage, fear, a sense of having been violated—all at once, all commingled.

He thought of the other Sullurh. What would he tell them? That their brethren from the stars had betrayed them? That Thul’s trust in the Ariantu had brought down this shame upon them?

Could he face that prospect? He didn’t think so. His standing in the community was all he had. Without that, he was nothing.

He had to strike back at the ones who had humiliated them. He had to regain for the Sullurh a measure of their self-respect.

But how?

Abruptly the answer came to him, as if delivered by the ancient gods of his people. And as he got up off his knees, he knew exactly what he had to do.

Chapter Eighteen

STEPHALEH REGARDED THE ANDROID. She had grown to like the inquisitive and talkative machine. Sometimes, in the hectic rush of events, she even forgot that he was a construction.

But she had been unprepared for his request. After all, if a seasoned diplomat like her, with all her proven instincts and tactics, couldn’t persuade the Ariantu to lay down their arms, what chance did an artificial being have?

Then again, she told herself, he can hardly fail more miserably than I have.

“All right,” she said finally. “You have my permission, Commander Data.”

The android nodded once. “Thank you, Ambassador.” Seating himself at her desk, he reengaged the communications channel with two deft taps on her keypad.

La Forge stood off to one side watching silently but intently. He almost looked as if he was holding himself back, Stephaleh noted. As if he’d have liked to offer some advice, but was restraining himself. She thought about that. Why would he hold back? Out of respect for Data’s rank? Or because of something more personal—a decision to let the artificial man stand on his own, perhaps?

“Ariantu,” said the android. “This is Commander Data. Please respond.”

Suddenly the screen filled with an image of the bridge of the Ariantu heartship—an image dominated by a single figure, though others stood or worked in the background.

“This is Arikka, paac mother,” said the main figure. She looked very much like the statuette that Coleridge had beamed up to Captain Picard—the one that Stephaleh had admired so much, but officially ignored. Arikka was long and graceful, with a wolflike snout and fierce eyes. Her attire was severe and ostentatious at the same time—the garb of a warrior, recognizable in any culture.

“It is about time that you presented me with a military authority,” said the Ariantu, “not some spineless civilian with no power to back up her words.”

Stephaleh flinched a little at the insult, but took it in her stride. Right now she had other things on her mind.

They obviously respected Data because of his title and his uniform, she noted. How interesting.

“Paac Mother,” said the android, his brow wrinkling ever so slightly, “I am not a mili—”

It was Geordi who stopped him, both hands raised. Silently, he mouthed the words: Play along, Data. You are military—for now.

Data immediately chose another entry into the dialogue.

“Paac Mother, it is our hope that we can resolve this conflict without bloodshed.”

Arikka’s eyes narrowed. “You speak strangely,” she said, “for a warrior.”

“Nonetheless, that is our desire.”

She looked at him. “Fine, Commander. You wish to avoid bloodshed? Then leave this world. Now.”

Data seemed unimpressed by the threat. “First of all,” he said calmly, “that is not possible. There are not enough transport vessels in the vicinity to evacuate all of Kirlosia. Second, we are not inclined to leave. At least not until your claim to this world has been verified.” A pause. “And the best way for you to do this is in face-to-face talks, which I am sure could be held right here in the embassy.”

Stephaleh was impressed. She could hardly have put it better herself.

On the monitor, the Ariantu seemed to be mulling over Data’s words. Was she actually considering beaming down? Had the android succeeded?

“You are not military,” concluded Arikka.

Stephaleh’s heart sank—along with Geordi’s, if his expression was any indication.

“You make the same inane noises as that other one,” added the paac mother. “The one you call ‘ambassador.’ ” She turned her head and spat. “There is nothing more to talk about. You will leave the planet now—or you will die. It is all the same to us.”

“You permit no room for compromise,” observed Data. “Certainly if there is a chance to avoid needless suffering—”

&n

bsp; The screen went dark.

“Well,” Geordi said, “at least they’re an open-minded bunch.”

Data turned to the ambassador. “I did not accomplish very much,” he said apologetically.

“That’s all right,” the Andorian assured him. “You came closer than I did. You have nothing to be ashamed of.”

But all the same, he had failed. Data’s attempt at negotiation had had a promising beginning, but it had ended the same as hers: in defeat.

Stephaleh glanced out her window. The panic in the streets was getting worse, and there was nothing she could do about it.

A beeping in the room. La Forge tapped his communicator. “Geordi here.”

“Any success with the Ariantu?” It was Worf’s voice; the ambassador could not help but recognize it.

“Not much. They’re a very . . . single-minded people. But I guess we’ll keep trying until a better option comes along.” He frowned. “Or until they make good on their threat—whichever comes first.”

At the K’Vin embassy, Worf was looking out a window, too. Given his proximity to street level, the chaos outside seemed even closer, more threatening. He growled low in his throat.

“What about the populace?” he asked Geordi.

“What about them? They’re scared to death. They’re smashing everything they can get their hands on—even each other, I’m afraid.”

“They must be kept in check,” said the Klingon.

“Sure. Got any suggestions?”

Worf considered the problem for a moment. “We could always shoot them—stun them unconscious—and stop the rampage.”

There was silence on the other end. “Worf,” said Geordi finally, “I don’t think Starfleet Command would approve of us phaser-stunning the whole Federation side of Kirlosia. Have you got any other ideas?”

DOOMSDAY WORLD

DOOMSDAY WORLD