- Home

- CARMEN CARTER, PETER DAVID, MICHAEL JAN FRIEDMAN

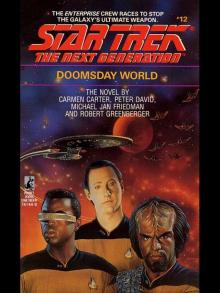

DOOMSDAY WORLD Page 11

DOOMSDAY WORLD Read online

Page 11

Besides, the demand for the stones was much greater on certain Federation worlds—where they were also illegal, though the penalties involved weren’t quite as high. Individuals of great wealth would pay dearly to sample the unique experience offered by the shrol’dinaggi. To taste century after dark, lusty century of primeval history—even if it was K’Vin history, and not their own. . . .

Arrangements had been made for shipping, receipt, payment—arrangements that called for Trimble to act only as a middleman, never to actually see or handle the merchandise. It was safer that way.

Suddenly Lars Trimble the struggling grain merchant had a chance to become Lars Trimble the shrol’dinaggi king—and a very rich man indeed.

In the end, however, he couldn’t do it. There was too much illegality on both sides of the fence. Too much risk—and too little sleep at night.

Maybe he just wasn’t greedy enough. Or maybe he didn’t want to have to explain to his children how he’d suddenly become so wealthy.

Then this spate of disasters had descended on Kirlosia. The destruction of the Commercial Trading Hall, the incidents of obvious sabotage that had followed—one on the K’Vin side, a second in the Federation sector, each one apparently a retaliation against the one before it.

And the irony was that even if Trimble had sold his soul to get the stones, the deal would never have gone through. With the city truly divided now, he could never have gotten payment to his K’Vin partner. Nor would the shrol’dinaggi have been smuggled out of K’Vin space on the basis of good faith alone.

But the fact that these incidents had taken place didn’t represent any kind of poetic justice—not to Lars Trimble. Because, thanks to them, his honest grain business had gone sour as well.

Did these troubles have anything to do with the Federation ship and the three officers it had left behind? He had heard whispers to that effect, even before the explosion in the museum.

Trimble looked around him at the sea of angry faces. He listened to their shouts. Apparently, they believed that the Federation officers had caused this. They weren’t sure how, but they seemed certain that there was a link.

And more and more, as he pressed toward the tower in the midst of them, so was Trimble. He found himself cursing the Starfleet officers out loud. And the louder he cursed, the more his apprehension seemed to diminish, to be swept aside in the sounds and scents of the mob’s mounting fury. The potential for violence hung low in the air, so thick that he could almost reach out and grasp it.

But somehow it no longer frightened Trimble. Now, it seemed almost exhilarating.

Up at the top of the steps, the embassy guards were drawing their phasers.

Data looked out the convex window of the ambassador’s office and noted the mood of the crowd at street level. Stephaleh had gone down to quiet them, but she had seemed to doubt her ability to do so.

Beside him, Worf grunted. “I still do not think it was wise for her to go down there alone.” His eyes narrowed beneath the bony ridge of his brow. “We should have gone along to protect her.”

Data turned toward him. “Perhaps, but she is not exactly alone. There are embassy guards holding the crowd at bay.”

The Klingon shook his massive head. “They are no protection. More likely than not, they have never used a phaser in their lives.”

The android saw that there was no arguing that point, so he changed tack. “In any case, it was the ambassador’s wish that we remain here in her office, since our presence on Kirlos is very much at the heart of the mob’s discontent.”

“Sure,” said Geordi, who had been pacing the room for the last several minutes. The chief engineer had been imbued with a manic energy since the death of his former mentor. “They don’t like what’s going on, so they find a convenient bunch of scapegoats.” He shot a glance in the direction of the window. “Did it ever occur to them that maybe we’re not too happy either? That . . .” For a moment, he seemed to have trouble getting the words out. “That maybe we’ve been hurt by all this, too?”

When Data first began his stint on the Enterprise, he would have answered those questions. Now—thanks in large part to Geordi’s tutelage—he recognized them as rhetorical. As a result, he did not respond to them.

“They are frightened,” said Zamorh. Data glanced over his shoulder; he had almost forgotten that the Sullurh was in the room with them.

Apparently Zamorh had not learned to distinguish between a rhetorical question and one that wanted answering.

“When one is frightened,” he went on, “one does not think clearly.”

Worf grunted again. “All the more reason to provide adequate protection. To shoot first and ask questions later.”

Data had the distinct impression that this argument was going around in circles. Rather than contribute to its momentum, he peered down again at the plaza, where the ambassador was just emerging.

Stephaleh had been in the diplomatic service for more years than she cared to count. She had helped negotiate treaties involving entire star systems, even empires.

But she had never faced a mob.

So why, she asked herself as she came out from the shelter of the embassy building, are you intent on facing one now? You, with your aches and pains, your complaints and your frailties? Should you not have remained behind your desk and allowed others to deal with this situation?

Perhaps she would have deferred to someone else—if there had been someone else to defer to. As it was, she had no choice but to face the mob herself.

The captain of her guards, the human named Powell, glanced at her as she approached the line that he and the others had established. He seemed surprised to see her.

“Put your phaser away,” said the ambassador. “And have the others do the same.”

With obvious reluctance, Powell complied. A few moments later the rest of the guards followed suit.

Stephaleh had hoped that the gesture would serve to quiet the crowd. To drain off some of the tension from the situation.

However, it had the opposite effect. Emboldened, the crowd grew louder. A couple of the merchants even climbed to the top of the steps, stopping only a couple of meters from where she stood.

But that was good, she told herself. It gave her someone through whom she could negotiate—a pair of intermediaries. It was a lot easier, she reflected, than trying to deal with a faceless mob.

Stephaleh acknowledged each of the intermediaries with a glance. Her antennae dipped forward—a reflex left over from the days when Andorians used them to communicate.

“What is the meaning of this?” she asked—with, she hoped, just the right mixture of indignation and curiosity.

“The meaning,” said one of the intermediaries, a tall and spindly Rhadamanthan, “is that something is going on here—something that already jeopardizes our livelihoods and that in time may jeopardize our lives.”

“That’s right,” said the other, a remarkably stocky specimen, even considering his Tellarite heritage. “If the Federation and the K’Vin are hatching a war here, we deserve to know why. And to be given some warning, so we can protect ourselves.”

The crowd roared its approval of those sentiments. Stoically, Stephaleh allowed the wave of emotion to crest and break before she responded.

Finally she held up her hands. “Listen to me,” she said, again addressing the intermediaries in particular. “There are no secret motives on Kirlos—not on the part of the Federation, at any rate.”

“No?” said the Tellarite. “Then it’s a coincidence that all of this began with the appearance of the Enterprise? And a coincidence also that the Starfleet officers were present when the trading hall fell—and again when the K’Vin embassy was nearly destroyed?”

“Give us credit for some intelligence,” said the Rhadamanthan. “It’s plain that Kirlos is being used as a pawn by the Federation, whether your superiors have chosen to inform you of it or not.”

The ambassador couldn’t help but be taken abac

k at the suggestion. Was it possible? Could the Federation be maneuvering behind her back?

No. She rejected the notion. That was not the way the Federation worked, especially not with one of its most trusted and experienced diplomats. If something was afoot, she would have been told of it.

“You are jumping to conclusions,” she told the Rhadamanthan, exhibiting a composure she did not feel. “We had nothing to do with the explosion at the K’Vin embassy. Nor, for that matter, do we have any proof that the attacks on the trading hall and the museum were K’Vin-inspired.”

“Of course not,” said the Tellarite. “Because those Starfleet spies staged all three incidents—to goad the K’Vin into warring with us!”

Another thunderous cheer from the crowd—this one longer than the first. Stephaleh began to feel the situation slipping out of her grasp. She had to find a new approach—and quickly.

“The Federation goads no one into war,” she rasped—giving her not-altogether-feigned anger free rein. “What could we possibly gain from it?”

“Only the Federation knows that,” sneered the Rhadamanthan.

Obviously intimidation wasn’t going to work, either. Things had already gone too far for that. Somehow she had to take the initiative.

Suddenly Stephaleh knew what she had to do. Without hesitation she started down the steps, cleaving a path between the Rhadamanthan and the Tellarite. Leaving them behind, open-mouthed, she descended into the roiling mass of the crowd. Powell uttered a protest; she ignored it.

At first, the ambassador had a feeling that the merchants might not yield to her approach. Then, at the very last second, the mob parted—and she made her way through it, slowly and purposefully, until she reached her goal.

He was a human—tall and lanky, with a reddish gold beard and small intensely blue eyes. When he saw the aged Andorian advancing on him, he took an involuntary step back, and would have taken more, apparently, if he’d had room.

Stephaleh didn’t stop until she was looking up into his ruddy, open face. His eyes became even smaller as he tried to decide why she was standing in front of him and not up at the top of the steps trying to calm the crowd.

This time she knew she had chosen well.

“I know you,” said the ambassador, in a soft voice that only those immediately surrounding her could hear. “You’re an honest man, trying to make an honest living. All you want is a peaceful place to do that.”

There were sharp complaints from all over the crowd, rising up like bubbles in the frothy waters of the Great Spring on Andor. And on their heels came calls for quiet, so everyone could hear.

But the ambassador didn’t raise her voice to make it any easier. She went on in that same subdued tone.

“What is your name?” she asked the human.

“Trimble,” he told her, as if mesmerized by her searching eyes, her gentle speech. “Lars Trimble.”

She nodded. “I make a promise to you, Lars Trimble. I make it here and now, not as the Federation’s ambassador to this world, but as Stephaleh n’Ehliarch, daughter of Andor. I promise you that I will do everything in my power to keep you and your family from harm. Everything. Do you believe me, Lars Trimble?”

The human regarded her. Numbly, he nodded.

Later he might remember the potential profits he had lost as a result of Kirlosia’s afflictions. He might even curse himself for not having throttled her when he had the chance.

But for now Lars Trimble was ensorcelled by the spotlight he’d abruptly found himself in. And by the invitation-to-trust demeanor it had taken Stephaleh years and worlds to perfect. Of course, it hadn’t hurt her credibility any that she’d meant every word of her promise to him.

“Good,” said the ambassador. “With your help, I will find us a way out of these troubles.” She placed her hand on his upper arm, squeezed it reassuringly. Then she turned and went back the way she had come.

Once again the crowd parted for her—this time a little more willingly. In her wake, she heard the shouts rise up again—pleas to know what she had said. Demands to know whom she had spoken to and why.

It had been a mistake to address the crowd’s leaders—she knew that now. Its leaders had been its head; by far, it had been wiser to appeal to its heart.

For a time now they would puzzle over what she had said to Lars Trimble. It would keep them off balance, keep their minds focused somewhere other than on their fears. At least temporarily, she had defused an explosive situation.

But it was hardly a permanent solution. She would have to get to the bottom of these incidents—before Lars Trimble and all the others like him took matters into their own hands.

Chapter Ten

ILUGH COULDN’T SLEEP, no matter how many times he shifted his position on the hard, molded mattress. It was no surprise—he had too much on his mind.

Specifically, the attack on the embassy—for he was certain it had been an attack and no accident. An act of sabotage that had endangered the lives of Ambassador Gregach and his entire staff.

Maybe the other guards could put it out of their minds. To them, this was just a job, an easy way to extend their military service without putting their hides on the line.

But they didn’t know Gregach as Ilugh did. As far as they were concerned, the ambassador was just another soft, slimy bureaucrat, living from one spilat dinner to the next.

Nor were they completely wrong—even Ilugh had to concede that. The ambassador dearly loved his homeworld delicacies.

However, he hadn’t always been like that. Once, the ambassador had been General Gregach, commander of the K’Vin forces at Titrikus IV and author of the victory over the invading Eluud. Once, the ambassador had been a hero of sorts, an up and coming star in the K’Vin military hierarchy.

Ilugh knew this because he had served under Gregach. Perhaps only as a common soldier, but he’d learned enough about the general to develop a healthy respect for him. Not only was Gregach a winner, but he logged his winnings without wasting K’Vin blood. Many of his peers had grown up in the school of Victory at Any Cost, but Gregach had been inclined to keep his losses to a minimum.

What Ilugh didn’t know was what had happened to take the luster off Gregach’s career—to earn him this unenviable position in the diplomatic service. Perhaps some enemy of his had gotten the upper hand in homeworld politics—who could know? Certainly not a lowly soldier.

But when Gregach was transferred here, Ilugh had asked for a transfer to Kirlos as well. He had applied for a berth as one of the general’s—no, the ambassador’—personal guards. Out of loyalty, out of respect, and though he would never say it out loud, out of affection—the kind one can only have for a great leader.

As he tossed and turned, Ilugh could hear Big Stragahn snoring at the other end of the barracks. It had started out as a small sound, on the edge of Ilugh’s consciousness, but now it was too loud to ignore.

And he knew it would only get worse. That was the way with Stragahn, particularly on nights when he remembered too well and had to get drunk to forget. Pretty soon everyone would be up, swearing softly at Stragahn, but too timid to wake him up for fear he’d put them through a wall.

If Ilugh had had any illusions about getting to sleep tonight, they had been dispelled. The only one who would sleep was Big Stragahn.

“Damn,” came the first curse, from the bunk below him. Onaht stuck his head out and peered up at Ilugh. “He’s at it again. This is the fifth night this month!”

Ilugh grunted. He leaned over, rested his tusks on his forearm. “You don’t remember—it used to be worse. When he first got here, Stragahn used to do this every other night. It’s only in the last couple of years that he’s mellowed.”

That didn’t seem to pacify Onaht. Not at all.

“I didn’t sign up for this wretched place to lie awake at night,” he groused. “If I’d wanted to do that, I could have asked for a berth on the Border.”

The snoring was getting louder, right on cue. T

here were bodies stirring all over the barracks.

Onaht muttered another curse—a rather colorful one that Ilugh hadn’t heard before. He had to chuckle at it.

“Go ahead and laugh,” said Onaht. “Maybe you can go without sleep; I can’t.” And with that he threw his legs over the side of the bed. He stood, glared in Stragahn’s direction, then started to walk.

“Wait a minute,” said Ilugh. He leaped down from his own bed and padded after Onaht on his bare feet. “Where do you think you’re going?”

Onaht didn’t look back. “To wake the soulless bastard,” he said.

Ilugh caught him by the arm. “Are you crazy?” he asked. “He’ll tear your arms off and feed them to you whole.”

Onaht snorted. “So what? Can it be worse than listening to this sound night after night?” And more roughly than he had a right to, he shrugged Ilugh off.

Ilugh bristled a little, feeling his tusks jut out. “Go ahead,” he said. “Be a young hothead—it’s your death song.”

He thought the other guard would turn back at the last. After all, no one woke Stragahn.

However, to his amazement, Onaht didn’t stop. He walked right up to the big one and shoved him.

“Shut up, you big lummox,” said Onaht, adding insult to injury. “We’re trying to get some rest here.”

Ilugh held his breath. So did Hulg and Tazradh, sitting up now in their bunks. In fact, the barracks building itself seemed to tense in anticipation.

But Stragahn didn’t move. He seemed oblivious to Onaht’s intervention.

Onaht had to be the luckiest soldier in the Hegemony.

Even more miraculous, Stragahn’s snoring had stopped. There was quiet now in the barracks—an almost eerie quiet.

Something about it made the skin crawl on the back of Ilugh’s neck. He walked past a self-satisfied Onaht and took a closer look at Stragahn.

Rolled him over—and saw the awful strangled expression on his face. The way his tongue lolled, the way his eyes appeared to pop out of their sockets.

“Gods,” whispered Onaht.

DOOMSDAY WORLD

DOOMSDAY WORLD